Learning by Doing: Pedagogy, Place, and Preservation

- November 18, 2020

- 10:22 am

- November 18, 2020

- 10:22 am

As we gear up for the 2020 NY Statewide Preservation Conference (December 1st-3rd), we’re diving back into past Conference topics with thoughts from some of our 2019 Conference speakers. This post is the second in a two-part series from the 2019 session, Preserving Tangible & Intangible Heritage: Frederick and Anna Murray Douglass as a Case Study. (Click here to read the first post).

by Juilee Decker, Ph.D.

As a public historian and faculty member at Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT), I am interested in making history relevant and useful in ways that can engage my students as well as the public. My research, scholarship, and teaching focus on sense of place and, in particular, monuments and memorials. In turn, one of my chief aims through my courses is to bring students closer to their community—to care about it and to have a want to understand, interpret, and preserve it—often through digital means. Often, we collaborate with community members, stakeholders, and colleagues, often employing digital tools to create spaces for learning, sharing, and preservation.

Given RIT’s historical roots in the liberal arts that became increasingly infused with emphasis on technical education, cooperative education, and career preparation since the institution’s founding in 1829, my courses enable students to engage in experiential learning – that is, learning by doing. Oftentimes, these areas intersect—the learning about place, monuments, and memorials create an awareness of preservation and enact a “digital doing.” By examining local history and collaborating on a public-facing project, students assess, research, author, revise, and synthesize material for online exhibitions and digital platforms. Their classroom experience serves as a place where they can identify with the broader community and cultivate an interest in (digitally) preserving their community. This is not to suggest that preservation of the bricks-and-mortar isn’t critical: it is, of course. But I hope that the work that my students and I engage in can contribute to and enrich the preservation practices already in place and those yet to be undertaken.

In each of the four instances describe below, students engaged in the classroom as well as libraries, archives, and other collecting institutions, in both the actual and virtual worlds through platforms where they assess, research, author, revise, and synthesize material for a public audience. The deliverables for these projects have, in some cases, supported and enhanced onsite exhibitions at RIT that the faculty of our program have curated; in other cases, the content is contributing to a community-led initiative. In all cases, however, the focus is on Rochester and its histories, as a means of engaging students with the city’s past and to bring those stories to the forefront of their classroom experience and to engender acts of digital preservation.

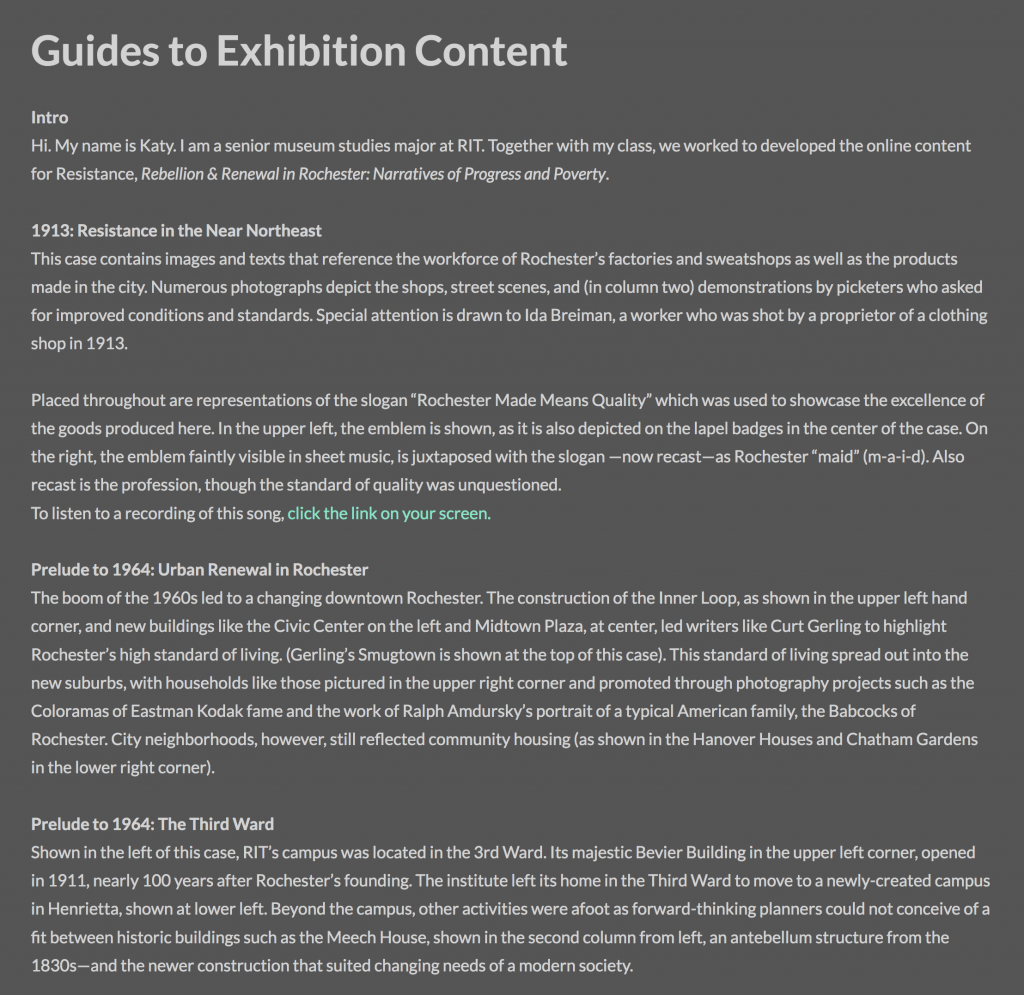

In terms of onsite exhibitions, students enrolled in my museum studies/public history courses have engaged in three Rochester-history-focused exhibition projects. The first of these, held in 2015, focused on “more than one hundred years of Rochester’s history to illuminate the co-existence of wealth and progress with poverty and lack of opportunity. In at least three separate periods, 1913, 1964, and 2015, these circumstances have spurred action in the form of resistance, rebellion, and renewal—while altogether jeopardizing the social fabric of the city.”[1] Students were charged with the task of developing online content to support this RIT faculty-curated exhibition mounted onsite on campus Resistance, Rebellion, and Renewal in Rochester: Narratives of Progress and Poverty (Fig. 1). The work of the faculty was supported and enhanced by the work of students who learned about Rochester history and made connections between historical vignettes featured in the exhibition and the broad arc of the city’s history—a commitment to connecting with a past that was unfamiliar, as the student body hails from all 50 states and more than 100 countries.

The students learned, for instance, how in 1913, Rochester garment workers organized a protest demanding eight-hour workdays, better wages, and union recognition. During this effort, a seventeen-year-old garment worker named Ida Breiman was shot and killed. Such incidents did not resonate with the students until we, as a class, unpacked what these moments might mean today, to us. In this series of discussions, a student made comparisons with the contemporary “Fight for $15” campaign, which aims to secure a more livable wage for low-wage workers—a point that resonates with RIT students who often seek part-time employment to support college expenses. Their uncovering of history and connecting it to today gave them ample latitude for making connections for their online audience (Fig. 2). To date, this exhibition is the most visited of our suite of student-curated digital exhibits.

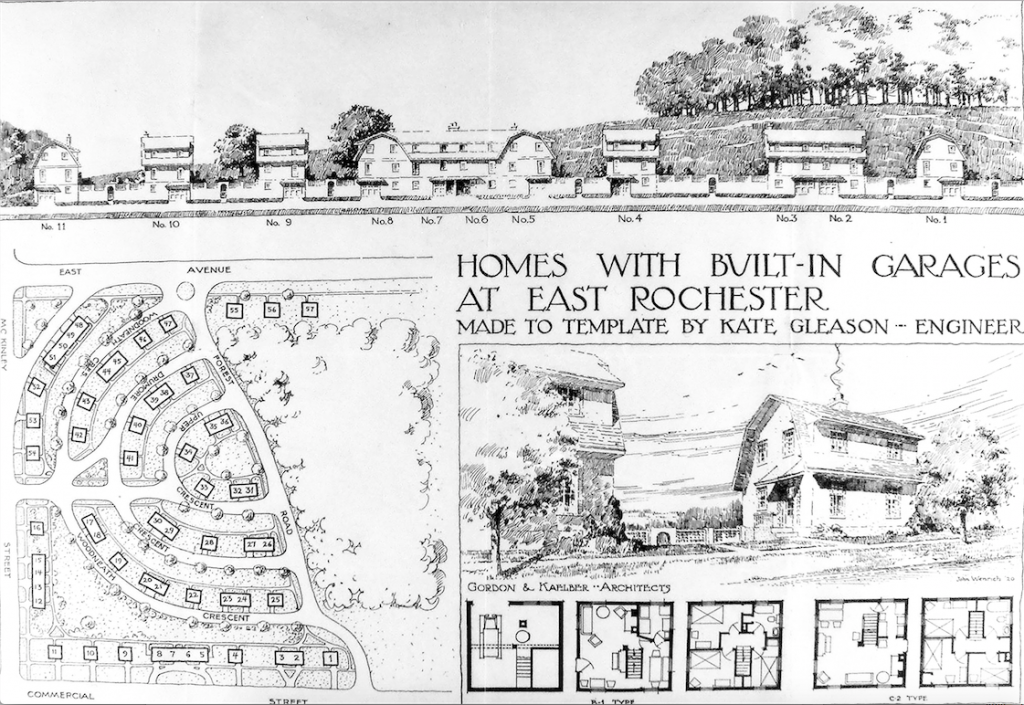

For the fall 2015 exhibition on Kate Gleason (1865–1933), Kate Gleason, Visionary: A Tribute on Her 150th Birthday (Fig. 3), students in one of my courses created digital content that reproduced onsite exhibition material, including a plan of homes that she designed in East Rochester (Fig 4) and a tea set that Gleason owned which is now in the collection of the RIT Archives (Fig. 5). They also created ancillaries that were entirely of their own visioning: a scavenger hunt, trivia questions, and a concordance related to recently restored film footage. The teams also worked together to prepare a social media campaign, website, and branding. Their messaging was carried further through “pop up” exhibitions mounted on campus in the various locations where academic courses that relate to Kate Gleason’s interests and success, including architecture, business, and engineering (Fig. 6).

The following semester, students took on an exhibition on NBA history, When Rochester Was Royal: Professional Basketball in Rochester, 1945–57 (Fig. 7),

in celebration of the 65th anniversary of the Royals having won the basketball championship. During the spring 2016, students created ancillaries, as they had been doing, but they also moved into more of a curatorial role by working in teams to develop content for three of the exhibition cases (Fig. 8). Combing through binders of photographs taken at games over the years, students began to make connections between basketball players from RIT (formerly Mechanics Institute) and the Rochester Royals (formerly the Seagram’s and Eber Brothers). At least two players from RIT were associated with the city’s first professional team: Stanley Witmeyer, class of 1936 ,and Francis (Frank) Beaty, class of 1941. These bits of info then led the students to learn more about the Eber Brothers, a local fruit, vegetable, and liquor company in the area at that time. The sense of community expanded from their immediate time period to the past, and with it a sense of place. Students came to realize that while the Royals plated at Edgerton Park Sports Arena for most of their career, the last of their games were played at the Community War Memorial, which is now Blue Cross Arena. They took an absence of knowledge about the shifting terrain of multiple basketball leagues in Rochester and converted that into an understanding of the dawn of television and the decline of the sport’s attendance locally which, in turn, meant that the Royals moved out of Rochester in 1957. The students’ exhibit work and digital archive provide locally-relevant content and give it a platform so that others can learn from it.

The final project that I will discuss shifts to an earlier part of Rochester history and makes use of a community-wide effort to celebrate, commemorate, and draw attention to Frederick Douglass, whose importance extends far beyond the city. During the spring 2018, as part of my own desire to activate students’ interest in Douglass’s connections to Rochester in the bicentennial year of his birth, I sought to highlight places in Rochester where Douglass was encountered and where he encountered others— where he lived and worked. To do so, I developed a project whereby students would research and re-trace Douglass’s steps so as to draw attention to these locations through the use of a mapping app called Clio, after the muse of history. Free to use, the web application enables anyone to upload content and to share information and images about historical sites in the United States. During January and February 2018, students examined primary materials from the Local History Division of the Rochester-Monroe County Public Library in order to draw up a list of “Douglass places.” As students identified sites, they filled in a spreadsheet to “choose” a location. Each student researched that location and developed content to put on the Clio platform in order to share the Douglass story in the context of that site.

Their project coincided with a simultaneous effort to “Re-Energize” the legacy of Frederick Douglass under the direction of Carvin Eison of Rochester Community Television; Bleu Cease from Rochester Contemporary Art Center; and Chris Christopher. A bicentennial commemoration committee curated key events, including an exhibition of contemporary art inspired by the Douglass monument and a community-wide celebration of the monument spearheaded by the “Big Shot” photographic team, a night-time community photography project produced by the school of photographic arts & sciences at RIT. (See my essay on Douglass and intangible heritage in the Fall 2019 Preservation magazine). For the students, their work had a broader purpose than the classroom assignment — they were community curators of history. Their assignment was due the week of Douglass’ birthday and was timed to coincide with the increasing interest of folks in Douglass sites (Fig. 9).

While I have only discussed a handful of the projects that we have developed over the past few years, the approach and outcomes for these experiences are similar across all of my courses. I ask what subject is in need of highlighting? How can we use digital tools to explicate history and to preserve it digitally? In addition to tackling a question of history, through such digital exhibitions and online work over these past few years, the actual and virtual worlds have become the locus of community and meaning-making. The student engagement in projects may be seen as a crucible of activity where we, as students and as a community, understand the stakes of contributing to a group project that had a further reach than a traditional assignment. By engaging students in the classroom as student-researchers and in the exhibit space and online as practitioners, these Rochester-focused projects have served as forms of collaborative engagement and peer-supported activity, public dissemination, and digital preservation.

Challenges come when working in project-based learning. While RIT’s heritage is tied to experiential learning, not every student will become engaged in the classroom. My course is not required of museum studies/public history majors; in fact, the majority of students in the course are enrolled to fulfill a general education requirement. They have many choices to fill that box in their curriculum plan. So rather than merely teach about what public history is, we are engaged in the work of doing it. We are learning by doing, which requires students buying in to deep engagement and immersion rather than only passively receiving information from a book or a lecture. While my course descriptions, syllabi, and other materials are explicit about the courses and expectations, sometimes this method of learning by doing surprises students.

It is rewarding to see the students rise to the challenge to make their work matter. With the projects outlined here, students—by and large—have felt an obligation to their classmates and/or the intended audience. The higher level of accountability to a community beyond the classroom space and engagement in its practices are meaningful learning experiences. And, such projects are a different level of work and accountability for me, as an instructor.

I love that I am able to work alongside students to teach them the tools of the trade, which include training in history research and writing, while also leading them through the process of creating and curating digital content. In this way, the “learning by doing” has two anchors: in the content of local history and in the application of digital tools. Students think critically about the subject (Rochester history—be in the two worlds of Rochester; visionary Kate Gleason’s life; the story of the Rochester Royals; and Frederick Douglass’s life and legacy) and in turn, interpret these stories to make meaning and share information for themselves and others. Through these carefully designed projects, I attempt to activate or enhance my students’ attention to place and preservation. They are learning by doing and, likewise, expanding their understanding of Rochester history while helping to (digitally) preserve it. It is my hope that such community-inspired learning opportunities offer potential for continuous, thriving engagement, and the potential to preserve—digitally—stories from the Rochester community, a place where students may only reside for their college years, but for whom the digital footprint will persist.

[1] Juilee Decker et al. “Introduction.” Resistance, Rebellion, and Renewal in Rochester: Narratives of Progress and Poverty. Web. https://progressandpovertyrochester.wordpress. com/exhibition/.

Acknowledgements:

I would like to acknowledge colleagues in the museum studies program who have collaborated on the onsite exhibitions from which I developed student projects with digital ancillaries. These colleagues include: Michael Brown, Tamar Carroll, Tina DaCosta Chapman, Rebecca DeRoo, Rebecca Edwards, and Tina Lent. Students in several courses over the past five years have worked tirelessly to create public-facing, preservation-inspired content. The students’ names are listed on each of the websites in the References section. Their efforts cannot be understated, and I truly believe there is a little bit of a preservationist in each of them. Finally, I would like to acknowledge the support of my college administration, in particular the College of Liberal Arts Dean’s Office administrators, LaVerne McQuiller Williams and Michael Laver.

Juilee Decker is an associate professor of history and program director in the college of liberal arts at RIT. She has authored or edited several books focused on museums, museum history, digital engagement. Her current project is an examination of monuments and memorials in the US which includes digitally mapping our national collection. Juilee earned her Ph.D. from the joint program at Case Western Reserve University and the Cleveland Museum of Art. She may be reached at jdgsh@rit.edu

SHARE